Description

“It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably for lack of what is found there.” ~ William Carlos Williams

By now, this fragment from one of Doctor Williams’s pastorals has become as well-known and widely circulated as “The Red Wheelbarrow.” Poets have always been the star reporters of inner space and, as with the best reporters, they tell us things we didn’t know before; or, closer to the point, things we at best vaguely suspected were there, but couldn’t pin down without a poet’s unholy combination of audacity and precision. There remain important things in our lives that stay “news” longer than whatever cable television, newsprint, or digital feeds tell us and poets can’t help but dig deeper for the truths beyond the reach of mere fact, especially the bastardized “facts” of what we’ve come to know as “fake news,” which has given human imagination a bum rap insofar as its usefulness for understanding the who, what, when, where, and how of our souls’ disparate passages. The poet is here to deliver news-that-stays-news and, if she knows what she’s doing, clears a path to that Truth-and-Beauty signpost John Keats identified centuries ago.

By now, this fragment from one of Doctor Williams’s pastorals has become as well-known and widely circulated as “The Red Wheelbarrow.” Poets have always been the star reporters of inner space and, as with the best reporters, they tell us things we didn’t know before; or, closer to the point, things we at best vaguely suspected were there, but couldn’t pin down without a poet’s unholy combination of audacity and precision. There remain important things in our lives that stay “news” longer than whatever cable television, newsprint, or digital feeds tell us and poets can’t help but dig deeper for the truths beyond the reach of mere fact, especially the bastardized “facts” of what we’ve come to know as “fake news,” which has given human imagination a bum rap insofar as its usefulness for understanding the who, what, when, where, and how of our souls’ disparate passages. The poet is here to deliver news-that-stays-news and, if she knows what she’s doing, clears a path to that Truth-and-Beauty signpost John Keats identified centuries ago.

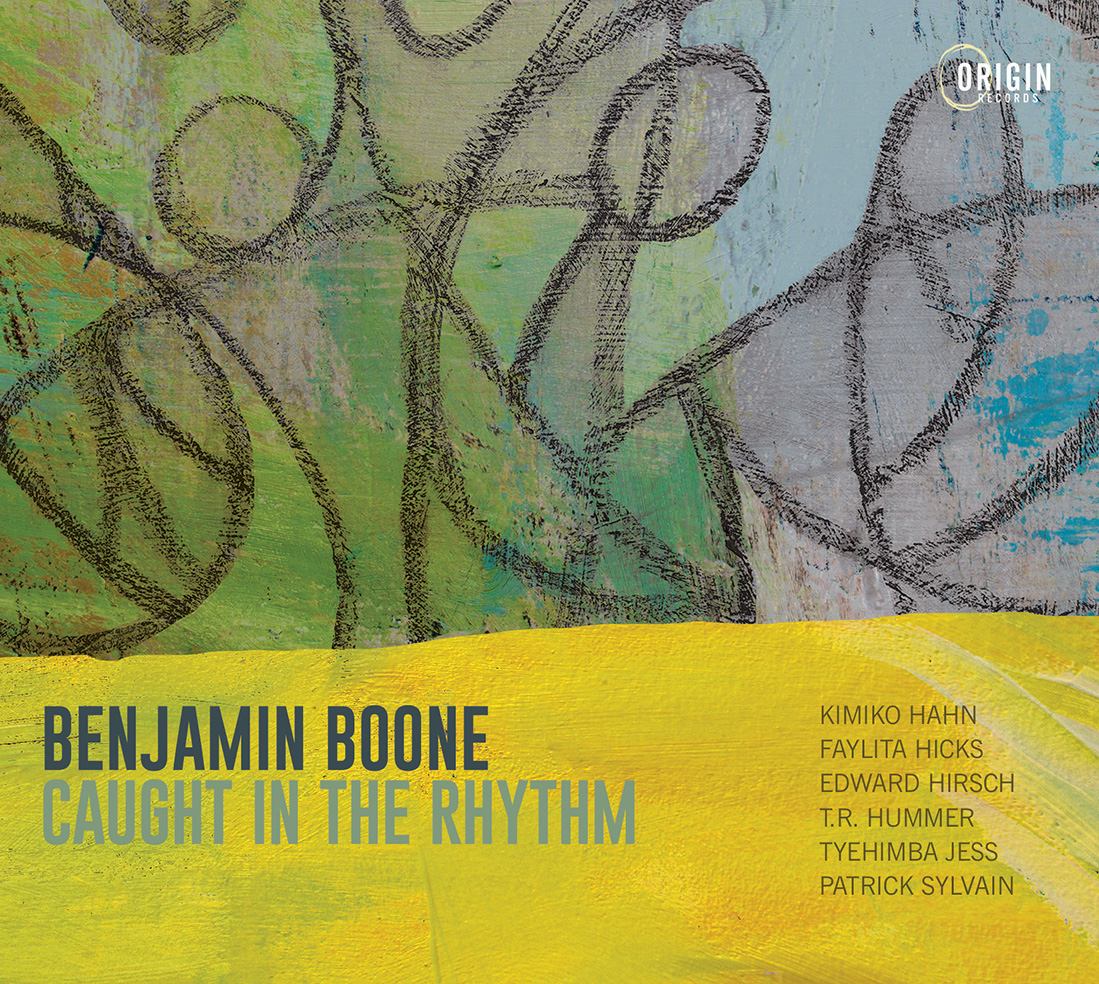

Think of Caught in the Rhythm, then, as an aural front page of dispatches, reveries, declamations, and narratives from past and present that tell you things you may have neglected, forgotten, or not known at all. As he has on three previous albums, Benjamin Boone has merged contemporary poets and their work with the roll, tempo, and spur-of-the-moment invention of jazz music, providing a framework for the spoken word that helps restore poetry’s quasi-musical primacy. As with 2020’s The Poets Are Gathering, Boone, once again the ringleader as arranger, composer, and saxophonist, sets off an exploding kaleidoscope of diverse voices, by turns raw, romantic, funny, elegiac, and emotionally accessible to listeners trying to sort their way through the swamp of the present day.

And, as before, Boone’s alto and soprano saxophones are both listening to and talking with the poetry itself, maintaining a solicitous negotiation with words, images and, most of all, the beat that propels each line. The glittering array of musicians who’ve come along with him on this ride are likewise conversant with each poem’s imperative. As before, the results are enrapturing, at times, breathtaking.

Caught in the Rhythm takes its title from a poem by Patrick Sylvain, a Haitian American poet-essayist-educator, whose eponymous contribution is, as with many other poems on this itinerary, a dance of imagery and rumination set in motion by what he describes at the outset as “a few beats sounded out of the earth” that wend their way through the poem—“tam doom tam”—in recurring, seemingly random intervals. Yet the “tam doom tam,” in whatever pattern of repetition, augments Sylvain’s haunting imagery as evocatively as trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire’s obbligatos sharpen our attentiveness to Sylvain’s evocation of “a circle of re-memory where the beloved refuse to stay drowned in silences.” A whole diaspora is summoned to life here and elsewhere in this rendering of Sylvain’s “Caught in the Rhythm” by both its words and its music.

A different but no less indelible manifestation of being captured by rhythm is presented by Faylita Hicks, who describe themselves as a “queer Afro-Latinx writer, spoken-word artist, and cultural strategist.” Hicks pries our eyes wide open with “HoodWitches,” a hard-as-tough-love throw-down in audacious tribute to “sistahs who snatch tracks and dodge ditches…” Boone’s alto saxophone submits to the poetry’s exuberance and, on this track and others, becomes a dancing partner to Hicks’s rhetoric, letting their vibrant wordplay lead him towards his own fire-breathing variations. Hicks carries these pyrotechnic rhythms to their arrangement of “We Bring the Soul to It,” where hip-hop beats break parts of the poem into riff patterns; the title itself becomes the organizing motif for everything else in that whirring evocation of street bravado and funky assertiveness.

Hicks also submits two different, but equally mordant perspectives on racial justice. “Dawg, What the Fuck Ima Do With a $20?” takes off from the circumstances leading to the 2020 murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. That the whole revolting (if ultimately transformative) event started with the accusation that Floyd tried to buy cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill sends Hicks on a vividly acerbic reverie on how $20 bills fit into some bad and good times in their own life and how, even with all the possible uses to be made of a $20 bill, human lives shouldn’t be priced like a laptop, a loaf of bread – or a carton of cigarettes. A deeper, bluer funk shrouds Hicks’s “ASMR Sleepcast: The Night After Being Released from the Rural County Jail.” Its imagery, by turns ominous and melancholy, of highway traffic swelling like waves under which “coyotes make long-distance calls with the dog in the apartment above me” evokes the desolation and bottled-up rage of having nowhere to go after sustaining personal injustice. And yet, as with most blues songs, there is profound release in the act of sending this still-life into the atmosphere like a coded warning. The trio of pianist Kevin Person Jr., bassist Richard Lloyd Giddens Jr., and drummer McKenna Reeve deftly navigate this austere arrangement.

The three poems gathered here by Mississippi native T.R. Hummer are steeped in ironic reverie and leavened by wry humor. The title of “Mississippi 1955 Confessional” emits an alarm to those who remember what had happened late that same summer (“somewhere between solstice and equinox”) in that same Deep South state to a Black Chicago boy named Emmett Till, whose name and lynching never emerge, but are present nevertheless. To the five-year-old white boy in this poem, delirious from fever, life is more a golden apparition of young white women (his sisters), wearing white sundresses, hovering over him while the wind is a “loving black hand” that he was “taught to believe isn’t even human.” The poet may be speaking to Till, or others like him, when he states “I’ve seen your face. I remember your name…” All the significant things shielded from us by our respective childhoods come back to haunt us as much as the guitar chords by Ben Monder and Eyal Maoz. One thinks of the line, “Angelic body of smoke with a guitar hidden in it” from another one of Hummer’s reveries herein, “You’ll Be Sorry.” Hummer’s “Anger Management” is more of a comedic relief in which its narrator is driven to the precipice of wrath when his dog chews up a beloved copy of Nietzsche’s writings and somehow is soothed knowing that, one way or another, the philosopher’s words will be regurgitated.

Besides Hicks, Hummer, and Sylvain, there are three other participants from The Poets Are Gathering session—Tyehimba Jess, Kimiko Hahn, and Edward Hirsch. Jess’s contribution, “Mercy,” transforms war itself into a sentient, staggering Thanos-like apocalypse beast “with a dirty coin jingle in its step…a hand of many lost hands, a palm of missing fingers.” The tread of this monster is tracked by

the chilling interplay of pianist Kenny Werner, drummer Ari Hoenig, bassist Corcoran Holt, and (especially) violinist Stefan Poetzsch. Hahn is represented by the riotously piquant (and pithy) “Olivia Suggests All the Women in Class Imagine Male Sexuality.” Your imagination could likely follow the path laid out by the words “unpredictable…/hard/long/and eel-like in appearance” with help from the humorously suggestive background music. Hahn’s enigmatic “Poem 836 from The Poems of Emily Dickinson” shares a track with “The Diviner,” a panorama of historic legacy and daily life in which fragments from the first poem are recited in class “to my undergraduate students, immigrant students, homeless students, working two-shifts students who likely get a more vivid classification, doing whatever it is they do outside our elegiac quadrangle.”

Edward Hirsch makes the most direct acknowledgment to the session’s jazz linkages with a moving paean to “Art Pepper,” appraising and lamenting the late alto saxophonist’s turbulent and, ultimately, triumphant life, marked by “years of being strung-out, years without speaking / Pauses and intervals, silence…” The presence of Greg Osby’s lyrical and fiery alto sax flowing throughout is its own homage to Pepper. And there is Hirsch’s “The Case Against Poetry,” whose title is turned about and subverted by the intervention of nature’s vagaries and a singing beggar on the streets of Prague.

Leave it to music, melding with shadow and light, to make the case for poetry. That’s what this album—and its varied supplications to the muse—are for.

GENE SEYMOUR